Zambia’s emergency support scheme highly dependent on international donors

Zambia was hit by the pandemic in times of a financial crisis. The central government debt was at 91.6% of GDP at the end of 2019, and in November 2020 the country defaulted on its sovereign dept. Unsurprisingly, there was little space for increased spending on social policy programmes to mitigate the side effects of the pandemic. In fact, the social sector’s share in the total budget fell from 29.4% in 2019 to 26.1% in 2020.

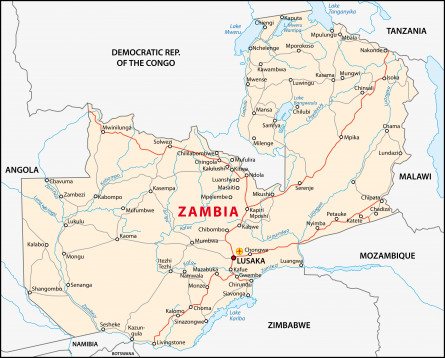

“Much of Zambia’s social policy response has focused on the formal sector, despite the country’s large informal sector, high unemployment rate and food insecurity across urban and rural areas”, Kate Pruce (Global Development Institute, University of Manchester) writes in her essay. The Covid-19 emergency cash transfer (ECT) was the most significant social policy intervention to support the poorest households to cope with shrinking income, rising unemployment, and in many areas, rising poverty and food insecurity. Introduced at the end of July 2020, it was supported and significantly funded by a range of partner organisations, including ILO, WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank. ECT combines cash and food assistance, providing 400 Zambian kwacha (ZMW) (roughly US$ 20) per month as well as food hampers for six months. The initiative covers 18 districts and reaching about 250,000 households.

Besides the ECT, the regular social cash transfer programme was also expanding in 2020, targeting 700,000 households. One has to bear in mind though, that the government had frequently missed its own targets in the past, underspending on the SCT programme by 67% in the last five years, Pruce writes.

For 2021 however, the government plans to more than double the budget for the regular social cash transfer programme from ZWM 1 billion (2020) to 2.3 billion (2021), increasing not only the number of beneficiaries, but also rising the benefit per household from ZMW 90 to 110. It is no coincidence that this huge spending surge will happen in the year of the general election (12 August 2021). But to put things into perspective: The budget for the controversial Farmer Input Support Programme (FISP) will also rise from ZWM 1.1 billion (2020) to 5.7 billion in 2021, although “the benefits of this spending mostly go to better-off farmers with larger landholdings, and these schemes have been shown to fare poorly in terms of cost-effectiveness and impacts on agricultural productivity”, Pruce notes in her essay. “The sustained and increased funding of FISP and FRA [Food Reserve Agency] demonstrates that these agricultural subsidy programmes retain their importance within the country’s political settlement and wider distributional regime. They therefore remain a priority for the government, in spite of evidence that they are not achieving their goals or supporting the poorest Zambians”, Pruce concludes.

Read Kate Pruce’s full report: Zambia’s Social Policy Response to Covid-19: Protecting the Poorest or Political Survival?

See the other parts of the series: CRC 1342 Covid-19 Social Policy Response Series